Founder of Bulletproof Musician

Fight or flight: When resistance feels worth it

When Noa Kageyama realized he didn’t love the thing he’d dedicated his life to, it was time to decide if the resistance he felt was the kind you push through or the kind that helps you choose a new path.

Words by Isa AdneyPhotography by Henry Thong

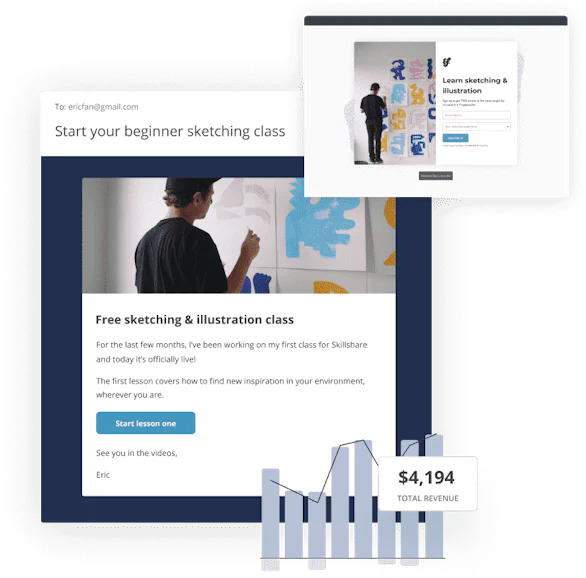

Support your growing business

Kit helps creators like you grow your audience, connect and build a relationship with that audience, and earn a living online by selling digital products.

Start a free 14-day trial

Isa Adney

Isa the Senior Writer at Kit and an award-winning writer, author, and producer who has profiled incredible creators and artists including Oscar, Grammy, Emmy, and Tony winners. When she’s not writing she’s probably walking her dog Stanley, working on her next book, or listening to the Hamilton soundtrack for the 300th time. (Read more by Isa)